Growing up, myself and my siblings were actively encouraged to appreciate and look after the world around us, as best we could. Every year we would pilgrimage to Stonehenge, in order to celebrate the Summer Solstice- the longest day of the year. Travelling to Stonehenge was always such an important part of our Solstice celebration and I was shocked to learn of the efforts taken in recent history to prevent public access to the site. In an attempt to ‘protect its heritage’, the stones were fenced off In 1985, causing a conflict nicknamed “Battle of the Beanfield”, where travellers to the site protested for the right to access the common land where Stonehenge stood. Today, public access to the stone circle is limited all year round, apart from occasions such as the Summer and Winter Solstices. On these days, thousands of people travel from all over the world to spend the night amongst the stones and then watch the sunrise on the longest/shortest days of the year. Upon reflection, this annual journey most definitely instilled a sense of connection to the landscape in us from an early age.

“The beauty of these sites is that there is a sense of shared ownership, physically and conceptually. Whatever your views about yourself or your country and humanity, you can project them onto these structures- Stonehenge especially.” (141).

Jeremy Deller, Radical Landscapes

Being fortunate enough to have lived in a house situated within a small village, of which the surrounding fields became an extended playground for us children, I can appreciate just how privileged we were to have access to so much green space throughout our childhood. The reality is that most people have limited access to nature, and the spaces we generally inhabit are hybrids of nature and the man-made (described as an “Edgeland” within the exhibition catalog for Badlands, 2008). My practice explores the hybridity of spaces and expresses an interest in land management, through an evaluation of our role within the landscape. Initially influenced by the welsh Landscape during my time as a student at Aberystwyth University, the landscape subject has since offered a way to explore my current surroundings, within my practice. Neither situated within a rural or urban area, my work presents the spaces in-between, possessing features both natural and man-made. I believe that this interest stems form my relocation to the Midlands, from Wales, and the contrasts between these locations.

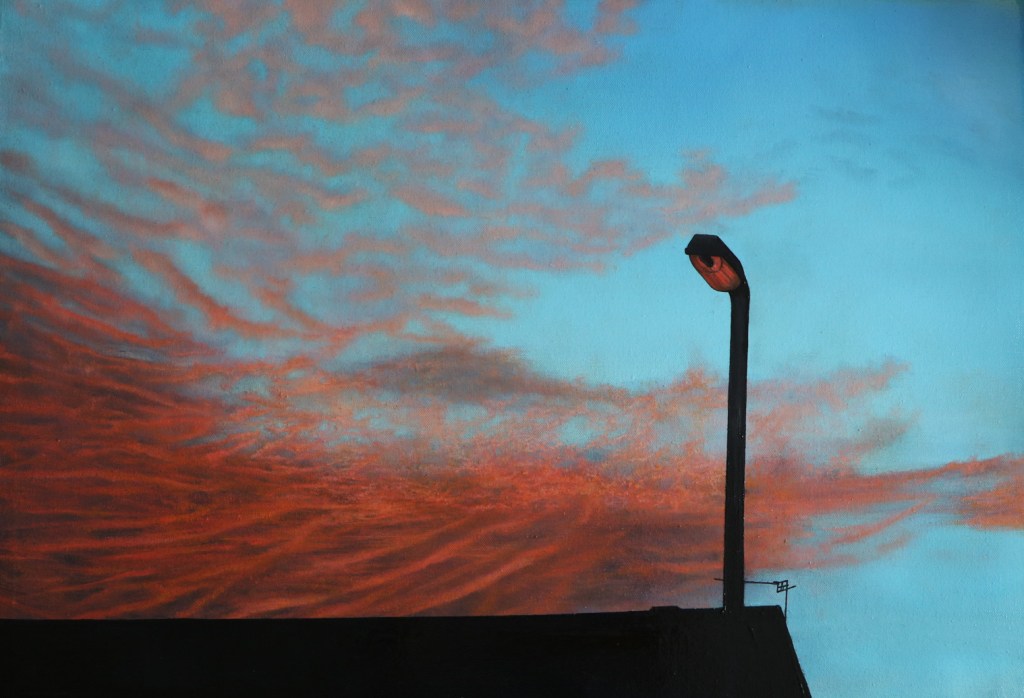

The painting My View at Twilight, 2020, was created just before I left Aberystwyth and presents a juxtaposition between the town and its mountainous surroundings. Featured in Sky Arts Landscape Artist of The Year earlier on this year, judge Kathleen Soriano commented: “we’ve got an artist finding something that is inconsequential but making it heroic.”. The Inclusion of contrasting structures (e.g., telephone poles) amongst natural landscapes has often been questioned, however, their presence is welcomed within my paintings, as they present a realistic contemporary existence. Without these features, my work could quite easily be lost within the landscapes of any previous century, thus their inclusion firmly places them within the current day. Birmingham on the Horizon was created as a follow-up of My View at Twilight, to express the difference of my surroundings today. The compositions I choose often present indistinct views, of which atmospherics play a significant role in their outcome as whole. As part of my reflection upon my arts based practice I have attempted to clarify here my interests, influences, and intentions as a landscape painter in 2022. This post comes at the end of my MA, when my final work is on display at Birmingham School of Art. Here, I will reflect upon my latests series of work, inspired by reading, exhibitions and first hand experience within the landscape.

The 2022 exhibition, Radical Landscapes, described as an “immersive exhibition [which] reveals how landscape art has become a progressive genre” (Tate), explores our connections to the rural landscapes of Britain. Despite the exhibition’s focus upon rural imagery, I found that some of the themes explored within the work on display related to my own interests as an artist. In particular, the environmental concern that is expressed through Yuri Pattison’s installation Sunset Provisioning, relates to my own motives for Red Sky at Night. Likewise referring to the way in which sunsets often create a sense of awe, the compositional choice for this painting was inspired by a statement made by my high school chemistry teacher: “Pollution can be amazing, can’t it?! (pointing up at the fluorescent sky}.

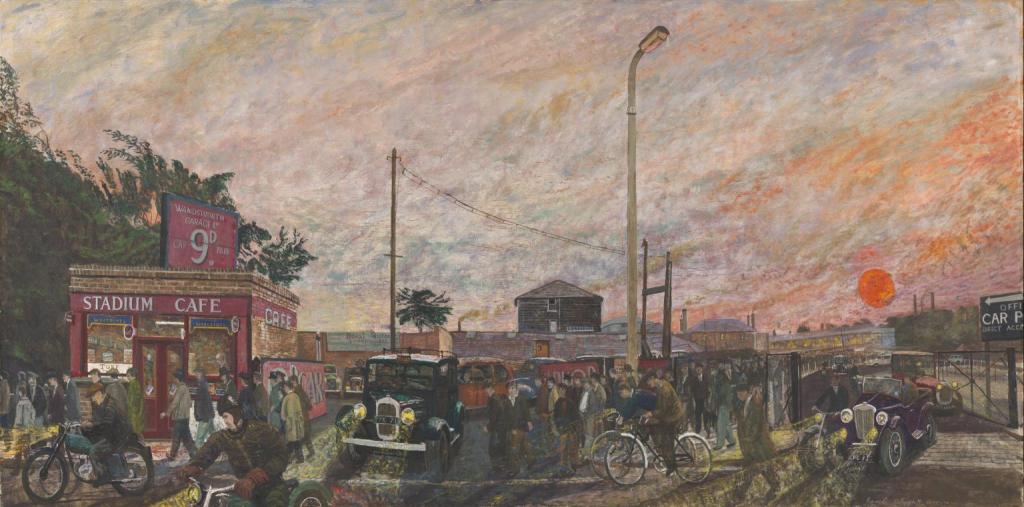

Conversely, the current touring exhibition The World We Live In, focuses upon urban life and our built-up surroundings. This display of work seeks to express the influence features of urban life (e.g., architecture, commuting and lights) have had on artists throughout the last century. Upon visiting the exhibition, I was able to see the works of artists Carel weight and George Shaw who have both provided creative inspiration throughout my undergrad and postgrad studies. Although Weight’s paintings often contain human life, his compositions are likewise directed by vertical structures within the scene, such as lampposts and telephone poles. It is also clear that both of these artists are keen to express a specific atmosphere within their paintings. Atmospherics have played a key role within the creation of my own work, and similarly to George Shaw, I have sourced much of my inspiration from Romanticism. Shaw’s distinct paintings present contemporary scenes through gothic imagery.

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/weight-the-dogs-t00095

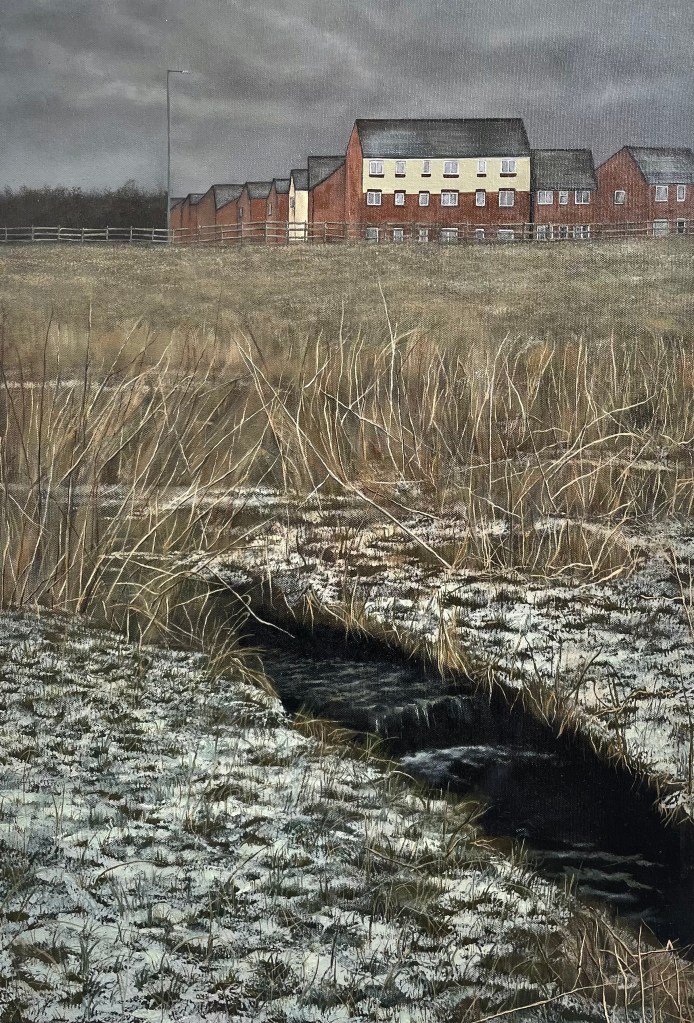

The work of the Pre-Raphaelites, who were likewise influenced by Romanticism, have captured my interest over the last few years. Keen to depict scenes which expressed a “truth to nature”, I follow suit in my rendition of the expanding estate, Field in the New Estate. A “moody” atmosphere, expressed by the dark depiction of the sky, is almost contradicted by the bright snow in the foreground. By ensuring that both the top and bottom half of the canvas were portrayed in detail, the scene describes the inevitable expansion of the site into its natural surroundings.

As briefly mentioned earlier, the Exhibition Badlands, which took place in 2008, gained my attention through its common interest in contemporary, varied landscapes. Curated as a way to aid its viewer in reconsidering the essential character of landscape today, my exploration into landscape continues on from the purpose of this exhibition, twelve years on. This display also referred to the ecological crisis through its selection of art and artists, one of them being Robert Adams. As part of the New Topographics movement, Adam’s photographs present the group’s common interest to address “the end of romantic nature and the erasure of boundaries between the human and the natural” and present the “convergence of man and nature”. (Markonish, 21). His work being a key interest throughout the duration of my postgraduate research, the landscapes Adams portrays are devoid of human life, however their presence is always evident. Despite the photographer’s clear shift away from traditional landscape representation, Denise Markonish, editor of Badlands catalog, describes his work as a “poetic sublime…not the heroic vista but the ability to look beyond the obvious and feel the landscape in his photographs as if you were there beside him”(Markonish, 25). I found this description intriguing, due to the sublime’s ties to traditional landscape representation and the hostility that is generally felt towards such imagery today. Alternatively, writer Curtis Wright advocates a “revival of the sublime as the only hope for art in a co-opted world.”(Markonish,85). With a focus upon the sublime once again, Wright expresses the possibility of going beyond the limits of the genre and exploring the imagination.

https://www.lensculture.com/radams

Ginger Strand, likewise believes that a revival in sublime imagery could be beneficial, specifically for environmental awareness. Describing it as a return to “aesthetic purpose”, Strand refers to the Romantic theory of landscapes to convey moral messages. This purpose seems very apt within our current climate: “Today with the environment imperilled, moral meaning has come back to the foreground.” (Markonish, 86). Strand also attempts to break the barrier between the city and the country as cultural opposites, describing their interconnectedness through their inability to exist without one another in contemporary society. This view is particularly interesting because of the interaction between both the urban and rural that is present within my own work.

Moving forward, I will continue to develop my painting practice, referring to the landscape for creative inspiration. I write this conclusion as I spend the day invigilating the gallery space of my MA degree show. A show filled with wonderfully diverse artworks, each expressing the unique personalities of all the students I have had the pleasure of working alongside, over the last two years.

References

Pih, Darren. Radical Landscapes: Art, Identity and activism. Tate, 2022. Print.

Markonish, Denise. Badlands : New Horizons in Landscape. Cambridge, Mass. ;: MIT, 2008. Print.

The End Of Time. https://artscouncilcollection.org.uk/artwork/end-time

Carel Weight, The Dogs. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/weight-the-dogs-t00095

https://www.lensculture.com/radams

https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-liverpool/radical-landscapes